Medicine:Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma

| Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Squamous-cell carcinoma of the skin, squamous-cell skin cancer, epidermoid carcinoma, squamous-cell epithelioma of the skin |

| |

| Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma tends to arise from actinic keratoses (premalignant lesions); surface is usually scaly and often ulcerates (as shown here). | |

| Specialty | Dermatology, plastic surgery, otorhinolaryngology |

| Symptoms | Hard lump with a scaly top or ulceration.[1] |

| Risk factors | Ultraviolet radiation, actinic keratosis, tobacco smoking, lighter skin, arsenic exposure, radiotherapy, poor immune system function, HPV infection[2] |

| Diagnostic method | Tissue biopsy[2][3] |

| Differential diagnosis | Keratoacanthoma, actinic keratosis, melanoma, warts, basal cell cancer[4] |

| Prevention | Decreased UV radiation exposure, sunscreen[5][6] |

| Treatment | Surgical removal, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy[2][7] |

| Prognosis | Usually good[5] |

| Frequency | 2.2 million (2015)[8] |

| Deaths | 51,900 (2015)[9] |

Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma (cSCC), or squamous-cell carcinoma of the skin, also known as squamous-cell skin cancer, is, with basal-cell carcinoma and melanoma, one of the three principal types of skin cancer.[10] cSCC typically presents as a hard lump with a scaly top layer, but it may instead form an ulcer.[1] Onset often occurs over a period of months.[4] Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma is more likely to spread to distant areas than basal cell cancer.[11] When confined to the outermost layer of the skin, a pre-invasive, or in situ, form of cSCC is known as Bowen's disease.[12][13]

The most significant risk factor for cSCC is high lifetime exposure to ultraviolet radiation from the sun.[2] Other risks include prior scars, chronic wounds, actinic keratosis, paler skin that sunburns easily, Bowen's disease, arsenic exposure, radiation therapy, tobacco smoking, poor immune system function, prior basal cell carcinoma, and HPV infection.[2][14][15] Risk from UV radiation is related to total exposure, rather than exposure early in life.[16] Tanning beds have become another frequent source of ultraviolet radiation.[16] Risk is also elevated in certain genetic skin disorders, such as xeroderma pigmentosum[17] and certain forms of epidermolysis bullosa.[18] cSCC begins from squamous cells found in the upper layers of the skin.[19] Diagnosis is often based on skin examination, and confirmed by tissue biopsy.[2][3]

In vivo and in vitro studies have shown that the upregulation of FGFR2, a subset of the fibroblast growth factor receptor (FGFR) immunoglobin family, has a critical role to play in the progression of cSCC cells.[20] Mutations in the TPL2 gene cause over-expression of FGFR2, which activates the mTORC1 and AKT pathways in both primary and metastatic cSCC cell lines. By using a chemical substance, called a "pan FGFR inhibitor", cell migration and cell proliferation in cSCC have been attenuated in vitro.[20]

Avoiding exposure to ultraviolet radiation and the use of sunscreen appear to be effective methods of preventing cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma.[5][6] Treatment is typically by surgical removal.[2] This can be by simple excision if the cancer is small; otherwise, Mohs surgery is generally recommended.[2] Other options may include application of cold and radiation therapy.[7] In cases in which distant spread has occurred, chemotherapy or biologic therapy may be used.[7]

As of 2015, about 2.2 million people worldwide have cSCC at any given time.[8] About 20% of all skin cancer cases consist of cSCC.[21] About 12% of males and 7% of females in the United States develop cSCC at some point in time.[2] While prognosis is usually good, when distant spread occurs five-year survival is ~34%.[4][5] In 2015, cSCC resulted in approximately 52,000 deaths globally.[9] The mean age at diagnosis is around 66 years.[4] Following the successful treatment of one case of cSCC, a person is at significant risk of developing further cSCC lesions.[2]

Signs and symptoms

SCC of the skin begins as a small nodule and as it enlarges the center becomes necrotic and sloughs and the nodule turns into an ulcer, and generally are developed from an actinic keratosis. Once keratinocytes begin to grow uncontrollably, they have the potential to become cancerous and produce cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma.[22]

- The lesion caused by cSCC is often asymptomatic

- Ulcer or reddish skin plaque that is slow growing

- Intermittent bleeding from the tumor, especially on the lip

- The clinical appearance is highly variable

- Usually the tumor presents as an ulcerated lesion with hard, raised edges

- The tumor may be in the form of a hard plaque or a papule, often with an opalescent quality, with tiny blood vessels

- The tumor can lie below the level of the surrounding skin, and eventually ulcerates and invades the underlying tissue

- The tumor commonly presents on sun-exposed areas (e.g. back of the hand, scalp, lip, and superior surface of pinna)

- On the lip, the tumor forms a small ulcer, which fails to heal and bleeds intermittently

- Evidence of chronic skin photodamage, as in multiple actinic keratoses (solar keratoses)

- The tumor grows relatively slowly

Spread

- Unlike basal-cell carcinoma (BCC), squamous-cell carcinoma (SCC) has a higher risk of metastasis.

- Risk of metastasis is higher clinically in SCC arising in scars, on the lower lips, ears, or mucosa, and occurring in immunosuppressed and solid organ transplant patients. Risk of metastasis is also higher in SCC that are > 2 cm in diameter, growth into the fat layer and along nerves, presence of lymphovascular invasion, poorly differentiated cell architecture on histology, or thickness greater than 6 mm.[23][24][25]

Causes

Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma is the second-most common cancer of the skin (after basal-cell carcinoma, but more common than melanoma). It usually occurs in areas exposed to the sun. Sunlight exposure and immunosuppression are risk factors for SCC of the skin, with chronic sun exposure being the strongest environmental risk factor.[26] There is a risk of metastasis starting more than 10 years[citation needed] after diagnosable appearance of squamous-cell carcinoma, but the risk is low,[specify] though much[specify] higher than with basal-cell carcinoma. Squamous-cell cancers of the lip and ears have high rates of local recurrence and distant metastasis.[27] In a recent study, it has also been shown that the deletion or severe down-regulation of a gene titled Tpl2 (tumor progression locus 2) may be involved in the progression of normal keratinocytes into becoming squamous-cell carcinoma.[28]

cSCC represents about 20% of the non-melanoma skin cancers; 80-90% of cSCCs with metastatic potential are located on the head and neck.[29]

Tobacco smoking also increases the risk for cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma.[14][30]

The vast majority of cSCC cases are located on exposed skin, and are often the result of ultraviolet exposure. cSCC usually occurs on portions of the body commonly exposed to the sun; the face, ears, neck, hands, or arms. The primary sign is a growing bump that may have a rough, scaly surface, and flat, reddish patches. Unlike basal-cell carcinoma, cSCC carries a higher risk of metastasis than does basal-cell carcinoma, and may spread to the regional lymph nodes,[31]

Erythroplasia of Queyrat (SCC in situ of the glans or prepuce in males,[32] M[33]:733[34]:656[35] or the vulva in females.[36]) may be induced by human papilloma virus.[37] It is reported to occur in the corneoscleral limbus.[38] Erythroplasia of Queyrat may also occur on the anal mucosa or the oral mucosa.[39]

Genetically, cSCC tumors harbor high frequencies of NOTCH and p53 mutations as well as less frequent alterations in histone acetyltransferase EP300, subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex PBRM1, DNA-repair deubiquitinase USP28, and NF-κB signaling regulator CHUK.[40]

Immunosuppression

People who have received solid organ transplants are at a significantly increased risk of developing squamous-cell carcinoma due to the use of chronic immunosuppressive medication.[41] While the risk of developing all skin cancers increases with these medications, this effect is particularly severe for cSCC, with hazard ratios as high as 250 being reported, versus 40 for basal cell carcinoma.[42] The incidence of cSCC development increases with time posttransplant.[43] Heart and lung transplant recipients are at the highest risk of developing cSCC due to more intensive immunosuppressive medications used.[44]

Cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma in individuals on immunotherapy or who have lymphoproliferative disorders (e.g. leukemia) tend to be much more aggressive, regardless of their location.[45] The risk of cSCC, and non-melanoma skin cancers generally, varies with the immunosuppressive drug regimen chosen. The risk is greatest with calcineurin inhibitors like cyclosporine and tacrolimus, and least with mTOR inhibitors, such as sirolimus and everolimus. The antimetabolites azathioprine and mycophenolic acid have an intermediate risk profile.[46]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is confirmed via skin biopsy of the tissue or tissues suspected to be affected by SCC. The pathological appearance of a squamous-cell cancer varies with the depth of the biopsy. For that reason, a biopsy including the subcutaneous tissue and basilar epithelium, to the surface is necessary for correct diagnosis. The performance of a shave biopsy (see skin biopsy) might not acquire enough information for a diagnosis. An inadequate biopsy might be read as actinic keratosis with follicular involvement. A deeper biopsy down to the dermis or subcutaneous tissue might reveal the true cancer. An excision biopsy is ideal, but not practical in most cases. An incisional or punch biopsy is preferred. A shave biopsy is least ideal, especially if only the superficial portion is acquired.[citation needed]

Histological characteristics

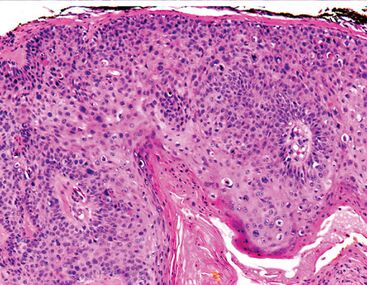

Histopathologically, the epidermis in cSCC in situ (Bowen's disease) will show hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis. There will also be marked acanthosis with elongation and thickening of the rete ridges. These changes will overly keratinocytic cells which are often highly atypical and may in fact have a more unusual appearance than invasive cSCC. The atypia spans the full thickness of the epidermis, with the keratinocytes demonstrating intense mitotic activity, pleomorphism, and greatly enlarged nuclei. They will also show a loss of maturity and polarity, giving the epidermis a disordered or "windblown" appearance.[citation needed]

Two types of multinucleated cells may be seen: the first will present as a multinucleated giant cell, and the second will appear as a dyskeratotic cell engulfed in the cytoplasm of a keratinocyte. Occasionally, cells of the upper epidermis will undergo vacuolization, demonstrating an abundant and strongly eosinophilic cytoplasm. There may be a mild to moderate lymphohistiocytic infiltrate detected in the upper dermis.[12]

Squamous-cell carcinoma in situ, showing prominent dyskeratosis and aberrant mitoses at all levels of the epidermis, along with marked parakeratosis.[12]

In situ disease

Bowen's disease is essentially equivalent to and used interchangeably with cSCC in situ, when not having invaded through the basement membrane.[12] Depending on source, it is classified as precancerous[13] or cSCC in situ (technically cancerous but non-invasive).[47][48] In cSCC in situ (Bowen's disease), atypical squamous cells proliferate through the whole thickness of the epidermis.[12] The entire tumor is confined to the epidermis and does not invade into the dermis.[12] The cells are often highly atypical under the microscope, and may in fact look more unusual than the cells of some invasive squamous-cell carcinomas.[12]

cSCC in situ, high magnification, demonstrating an intact basement membrane.[12]

Erythroplasia of Queyrat is a particular type of Bowen's disease that can arise on the glans or prepuce in males,[32][33]:733[34]:656[35] and the vulva in females.[36] It mainly occurs in uncircumcised males,[36][49] over the age of 40.[39]

Invasive disease

In invasive cSCC, tumor cells infiltrate through the basement membrane. The infiltrate can be somewhat difficult to detect in the early stages of invasion: however, additional indicators such as full thickness epidermal atypia and the involvement of hair follicles can be used to facilitate the diagnosis. Later stages of invasion are characterized by the formation of nests of atypical tumor cells in the dermis, often with a corresponding inflammatory infiltrate.[12]

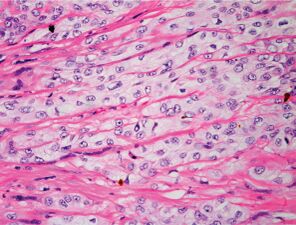

Superficially invasive cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. These lesions often do not show the marked pleomorphism and atypical nuclei of cSCC in situ, but manifest early keratinocyte invasion of the dermis.[12]

High magnification demonstrates the pleomorphism of the invading keratinocytes[12]

Degree of differentiation

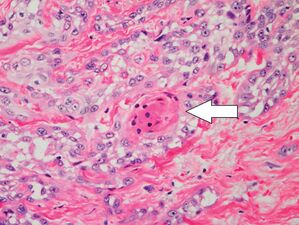

Well-differentiated (yet invasive) cSCC, showing prominent keratinization. It may form pearl-like structures where dermal nests of keratinocytes attempt to mature in a layered fashion. Well-differentiated cSCC has slightly enlarged hyperchromatic nuclei with abundant amounts of cytoplasm. Intercellular bridges will frequently be visible.[12]

Moderately differentiated lesions of invasive cSCC show much less organization and maturation with significantly less keratin formation.[12]

Poorly differentiated, where attempts at keratinization are often no longer evident. This is a clear-cell squamous-cell carcinoma. The dysplastic cells infiltrated cords through the dermis. Poorly differentiated cSCC has greatly enlarged pleomorphic nuclei showing a high degree of atypia and frequent mitoses.[12]

Poorly differentiated clear-cell squamous-cell carcinoma. For this type of cSCC, immunostains will likely be required to classify it unless other areas of the tumor show obvious squamous-cell features such as seen here (arrow).

Prevention

Appropriate sun-protective clothing, use of broad-spectrum (UVA/UVB) sunscreen with at least SPF 50, and avoidance of intense sun exposure may prevent skin cancer.[50] A 2016 review of sunscreen for preventing cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma found insufficient evidence to demonstrate whether it was effective.[51]

Management

Most cutaneous squamous-cell carcinomas are removed with surgery. A few selected cases are treated with topical medication. Surgical excision with a free margin of healthy tissue is a frequent treatment modality. Radiotherapy, given as external beam radiotherapy or as brachytherapy (internal radiotherapy), can also be used to treat cSCC. There is little evidence comparing the effectiveness of different treatments for non-metastatic cSCC.[52]

Mohs surgery is frequently utilized; considered the treatment of choice for squamous-cell carcinoma of the skin, physicians have also utilized the method for the treatment of squamous-cell carcinoma of the mouth, throat, and neck.[53] An equivalent method of the CCPDMA standards can be utilized by a pathologist in the absence of a Mohs-trained physician. Radiation therapy is often used afterward in high risk cancer or patient types.[54] Radiation or radiotherapy can also be a standalone option in treating cSCC. As a non-invasive option brachytherapy serves a painless possibility to treat in particular but not only difficult to operate areas like the earlobes or genitals. An example of this kind of therapy is the high-dose brachytherapy Rhenium-SCT which makes use of the beta rays emitting property of rhenium-188. The radiation source is enclosed in a compound which is applied to a thin protection foile directly over the lesion. This way the radiation source can be applied to complex locations and minimize radiation to healthy tissue.[55]

After removal of the cancer, closure of the skin for patients with a decreased amount of skin laxity involves a split-thickness skin graft. A donor site is chosen and enough skin is removed so that the donor site can heal on its own. Only the epidermis and a partial amount of dermis is taken from the donor site which allows the donor site to heal. Skin can be harvested using either a mechanical dermatome or Humby knife.[56]

Electrodessication and curettage (EDC) can be done on selected squamous-cell carcinoma of the skin. In areas where cSCC is known to be non-aggressive, and where the patient is not immunosuppressed, EDC[clarification needed] can be performed with good to adequate cure rate.[57]

Treatment options for cSCC in situ (Bowen's disease) include photodynamic therapy with 5-aminolevulinic acid, cryotherapy, topical 5-fluorouracil or imiquimod, and excision. A meta-analysis showed evidence that PDT is more effective than cryotherapy and has better cosmetic outcomes. There is generally a lack of evidence comparing the effectiveness of all treatment options.[13]

High-risk squamous-cell carcinoma, as defined by that occurring around the eye, ear, or nose, is of large size, is poorly differentiated, and grows rapidly, requires more aggressive, multidisciplinary management.

Nodal spread:

- Surgical block dissection if palpable nodes or in cases of Marjolin's ulcers but the benefit of prophylactic block lymph node dissection with Marjolin's ulcers is not proven.

- Radiotherapy

- Adjuvant therapy may be considered in those with high-risk cSCC even in the absence of evidence for local metastasis. Imiquimod (Aldara) has been used with success for squamous-cell carcinoma in situ of the skin and the penis, but the morbidity and discomfort of the treatment is severe. An advantage is the cosmetic result: after treatment, the skin resembles normal skin without the usual scarring and morbidity associated with standard excision. Imiquimod is not FDA-approved for any squamous-cell carcinoma.

In general, squamous-cell carcinomas have a high risk of local recurrence, and up to 50% do recur.[58] Frequent skin exams with a dermatologist is recommended after treatment.

Prognosis

The long-term outcome of squamous-cell carcinoma is dependent upon several factors: the sub-type of the carcinoma, available treatments, location and severity, and various patient health-related variables (accompanying diseases, age, etc.). Generally, the long-term outcome is positive, with a metastasis rate of 1.9-5.2% and a mortality rate of 1.5-3.4%.[25][59][60]

When it does metastasize, the most commonly involved organs are the lungs, brain, bone and other skin locations.[61] Squamous-cell carcinoma occurring in immunosuppressed people (such as those with organ transplant, human immunodeficiency virus infection, or chronic lymphocytic leukemia) the risk of developing cSCC and having metastasis is much higher than the general population.[62]

One study found squamous-cell carcinoma of the penis had a much greater rate of mortality than some other forms of squamous-cell carcinoma, that is, about 23%,[63] although this relatively high mortality rate may be associated with possibly latent diagnosis of the disease due to patients avoiding genital exams until the symptoms are debilitating, or refusal to submit to a possibly scarring operation upon the genitalia.

Epidemiology

The incidence of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma continues to rise around the world. This is theorized to be due to several factors; including an aging population, a greater incidence of those who are immunocompromised and the increasing use of tanning beds.[25]

A recent study estimated that there are between 180,000 and 400,000 cases of cSCC in the United States in 2013.[65] Risk factors for cSCC varies with age, gender, race, geography, and genetics. The incidence of cSCC increases with age and with those 75 years or older eing at a 5-10 times increased risk of developing cSCC as compared with those who are younger than 55 years old.[25] Males are affected with cSCC at a ratio of 3:1 in comparison to females.[25] Those who have light skin, red or blonde hair and light colored eyes are also at increased risk.[25]

Squamous-cell carcinoma of the skin can be found on all areas of the body but is most common on frequently sun-exposed areas, such as the face, legs and arms.[66] Solid organ transplant recipients (heart, lung, liver, pancreas, among others) are also at a heightened risk of developing aggressive, high-risk cSCC. There are also a few rare congenital diseases predisposed to cutaneous malignancy. In certain geographic locations, exposure to arsenic in well water[67] or from industrial sources may significantly increase the risk of cSCC.[26]

Additional images

See also

- List of cutaneous conditions associated with increased risk of nonmelanoma skin cancer

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Primary Care: The Art and Science of Advanced Practice Nursing. F.A. Davis. 2011. p. 242. ISBN 9780803626478. https://books.google.com/books?id=RR1hAQAAQBAJ&pg=PA242.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 "Skin Cancer Epidemiology, Detection, and Management". The Medical Clinics of North America 99 (6): 1323–1335. November 2015. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2015.06.002. PMID 26476255.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Skin Cancer Treatment" (in en). 21 June 2017. https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/patient/skin-treatment-pdq.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 (in en) Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2017 E-Book: 5 Books in 1. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2016. p. 1199. ISBN 9780323448383. https://books.google.com/books?id=rRhCDAAAQBAJ&pg=PA1199. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 World Cancer Report 2014.. World Health Organization. 2014. pp. Chapter 5.14. ISBN 978-9283204299.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "UV protection and sunscreens: what to tell patients". Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine 79 (6): 427–436. June 2012. doi:10.3949/ccjm.79a.11110. PMID 22660875.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Skin Cancer Treatment" (in en). 21 June 2017. https://www.cancer.gov/types/skin/patient/skin-treatment-pdq#link/_119_toc.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Vos, Theo et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1545–1602. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31678-6. PMID 27733282.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Wang, Haidong et al. (October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015". Lancet 388 (10053): 1459–1544. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(16)31012-1. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ "Skin Cancer Treatment (PDQ®)". 2013-10-25. http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/skin/HealthProfessional/page1/AllPages.

- ↑ "Epidemiology and economic burden of nonmelanoma skin cancer". Facial Plastic Surgery Clinics of North America 20 (4): 419–422. November 2012. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2012.07.004. PMID 23084294.

- ↑ 12.00 12.01 12.02 12.03 12.04 12.05 12.06 12.07 12.08 12.09 12.10 12.11 12.12 12.13 "Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review". Journal of Skin Cancer 2011: 210813. 2011. doi:10.1155/2011/210813. PMID 21234325.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

This article incorporates text available under the CC BY-SA 3.0 license.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 "Interventions for cutaneous Bowen's disease". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2016 (6): CD007281. June 2013. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007281.pub2. PMID 23794286.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "Basal and Squamous Cell Skin Cancer Risk Factors". American Cancer Society. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/basal-and-squamous-cell-skin-cancer/causes-risks-prevention/risk-factors.html.

- ↑ "Skin Cancer for the Plastic Surgeon". Textbook of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery (1 ed.). UCL Press. 2016. pp. 61–76. doi:10.2307/j.ctt1g69xq0.9. ISBN 978-1-910634-39-4.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "Ultraviolet radiation". Chronic Diseases in Canada 29 (Suppl 1): 51–68. 2010. doi:10.24095/hpcdp.29.S1.04. PMID 21199599.

- ↑ "Xeroderma pigmentosum". Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 6 (1): 70. November 2011. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-70. PMID 22044607.

- ↑ "Epidermolysis bullosa". Nature Reviews. Disease Primers 6 (1): 78. September 2020. doi:10.1038/s41572-020-0210-0. PMID 32973163.

- ↑ "NCI Dictionary of Cancer Terms". 2011-02-02. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/dictionaries/cancer-terms?cdrid=46595.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 "Fibroblast growth factor receptor promotes progression of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma". Molecular Carcinogenesis 58 (10): 1715–1725. October 2019. doi:10.1002/mc.23012. PMID 31254372.

- ↑ "Diagnosis and treatment of invasive squamous cell carcinoma of the skin: European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline". European Journal of Cancer 51 (14): 1989–2007. September 2015. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.110. PMID 26219687.

- ↑ H, Carlos (2022-09-10). "How serious is a squamous-cell carcinoma?" (in en-US). https://www.curadermbcc.eu/blog/squamous-cell-carcinoma/.

- ↑ "Risk Factors for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Recurrence, Metastasis, and Disease-Specific Death: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". JAMA Dermatology 152 (4): 419–428. April 2016. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2015.4994. PMID 26762219.

- ↑ "NCCN Guidelines® Insights: Squamous Cell Skin Cancer, Version 1.2022". Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network 19 (12): 1382–1394. December 2021. doi:10.6004/jnccn.2021.0059. PMID 34902824.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 25.5 Wysong, Ashley (15 June 2023). "Squamous-Cell Carcinoma of the Skin". New England Journal of Medicine 388 (24): 2262–2273. doi:10.1056/NEJMra2206348. PMID 37314707.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 "MD Consult - Important Notice". http://www.mdconsult.com/das/pdxmd/body/107722350-3/761088681?type=med&eid=9-u1.0-_1_mt_1014682.

- ↑ "Squamous Cell Carcinoma". 25 December 2010. http://www.aad.org/public/publications/pamphlets/sun_squamous.html.

- ↑ "Loss of tumor progression locus 2 (tpl2) enhances tumorigenesis and inflammation in two-stage skin carcinogenesis". Oncogene 30 (4): 389–397. January 2011. doi:10.1038/onc.2010.447. PMID 20935675.

- ↑ "Squamous cell carcinoma: 2021 updated review of treatment". Dermatologic Therapy 35 (4): e15308. January 2022. doi:10.1111/dth.15308. PMID 34997811.

- ↑ "Relation between smoking and skin cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology 19 (1): 231–238. January 2001. doi:10.1200/JCO.2001.19.1.231. PMID 11134217.

- ↑ "Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma: Practice Essentials, Background, Pathophysiology". 28 June 2016. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1965430-overview.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Lookingbill and Marks' principles of dermatology (4th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier. 2006. p. 63. ISBN 978-1-4160-3185-7.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill, Medical Pub. Division. 2003. ISBN 978-0-07-138076-8.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. 2006. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. 2007. pp. 1050. ISBN 978-1-4160-2999-1.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Sexually transmitted infections diagnosis, management, and treatment. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones & Bartlett Learning. 2012. p. 109. ISBN 9781449619848. https://books.google.com/books?id=prC2AgAAQBAJ&pg=PA109.

- ↑ "Erythroplasia of queyrat: coinfection with cutaneous carcinogenic human papillomavirus type 8 and genital papillomaviruses in a carcinoma in situ". The Journal of Investigative Dermatology 115 (3): 396–401. September 2000. doi:10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00069.x. PMID 10951274.

- ↑ "Bowen's Disease". Pakistan Journal of Ophthalmology 14 (1): 37–38. 1998. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265972111.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 European handbook of dermatological treatments (2nd ed.). Berlin [u.a.]: Springer. 2003. p. 169. ISBN 978-3-540-00878-1. https://books.google.com/books?id=BXmpcf70a3oC&pg=PA169.

- ↑ Chang, Darwin; Shain, A. Hunter (2021-07-16). "The landscape of driver mutations in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma". npj Genomic Medicine 6 (1): 61. doi:10.1038/s41525-021-00226-4. ISSN 2056-7944. PMID 34272401.

- ↑ Chang, Darwin; Shain, A. Hunter (2021-07-16). "The landscape of driver mutations in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma" (in en). npj Genomic Medicine 6 (1): 61. doi:10.1038/s41525-021-00226-4. ISSN 2056-7944. PMID 34272401.

- ↑ "Nonmelanoma skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: update on epidemiology, risk factors, and management". Dermatologic Surgery 38 (10): 1622–1630. October 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1524-4725.2012.02520.x. PMID 22805312.

- ↑ "Skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients: advances in therapy and management: part I. Epidemiology of skin cancer in solid organ transplant recipients". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 65 (2): 253–261. August 2011. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2010.11.062. PMID 21763561.

- ↑ Chockalingam, Ramya; Downing, Christopher; Tyring, Stephen K. (June 2015). "Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas in Organ Transplant Recipients" (in en). Journal of Clinical Medicine 4 (6): 1229–1239. doi:10.3390/jcm4061229. ISSN 2077-0383. PMID 26239556.

- ↑ "Squamous Cell Carcinoma: What it Looks Like". SkinCancerNet. American Academy of Dermatology. 2008. http://www.skincarephysicians.com/skincancernet/squamous_cell_carcinoma.html.

- ↑ "Skin cancer in organ transplant recipients: effects of immunosuppressive medications on DNA repair". Experimental Dermatology 21 (1): 2–6. January 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0625.2011.01413.x. PMID 22151386.

- ↑ Pathology of Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma and Bowen Disease. 3 April 2021. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1960631-overview. Updated: Jun 11, 2019

- ↑ "Bowen's disease". 17 October 2017. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/bowens-disease/. Page last reviewed: 21 May 2019

- ↑ The Merck manual of medical information. Whitehouse Station, N.J: Merck Research Laboratories. 1997. p. 1057. ISBN 0911910875. https://archive.org/details/merckmanualofmed00berk/page/1057.

- ↑ "Ultraviolet radiation". Chronic Diseases in Canada 29 (Suppl 1): 51–68. 2010. doi:10.24095/hpcdp.29.S1.04. PMID 21199599.

- ↑ "Sun protection for preventing basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 7 (9): CD011161. July 2016. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011161.pub2. PMID 27455163.

- ↑ "Interventions for non-metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the skin". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (4): CD007869. April 2010. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007869.pub2. PMID 20393962.

- ↑ Mohs Surgery, Fundamentals and Techniques. Mosby. 1999.

- ↑ "A Systematic Review of Primary, Adjuvant, and Salvage Radiation Therapy for Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma" (in en-US). Dermatologic Surgery 47 (5): 587–592. May 2021. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000002965. PMID 33577212.

- ↑ "High dose brachytherapy with non sealed 188Re (rhenium) resin in patients with non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSCs): single center preliminary results". European Journal of Nuclear Medicine and Molecular Imaging 48 (5): 1511–1521. May 2021. doi:10.1007/s00259-020-05088-z. PMID 33140131.

- ↑ [1], Hallock G. Squamous Cell Carcinoma Excision from Right Forearm with Split-Thickness Skin Graft from the Thigh. J Med Ins. 2020;2020(290.16) doi:https://jomi.com/article/290.16

- ↑ "Basal Cell and Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinomas: Diagnosis and Treatment". American Family Physician 102 (6): 339–346. September 2020. PMID 32931212. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32931212.

- ↑ "Transferring anterior occlusal guidance to the articulator". The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry 61 (3): 282–285. March 1989. doi:10.1016/0022-3913(89)90128-5. PMID 2921745.

- ↑ "[Risk of cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas: the role of clinical and pathological reports]". Revue Médicale Suisse 8 (335): 743–746. April 2012. PMID 22545495.

- ↑ "Analysis of risk factors determining prognosis of cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma: a prospective study". The Lancet. Oncology 9 (8): 713–720. August 2008. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70178-5. PMID 18617440.

- ↑ "Not Just Skin Deep: Distant Metastases from Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma". The American Journal of Medicine 130 (8): e327–e328. August 2017. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2017.02.031. PMID 28344135.

- ↑ "Cancer in the transplant recipient". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine 3 (7): a015677. July 2013. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a015677. PMID 23818517.

- ↑ "Clinical and pathologic factors of prognostic significance in penile squamous cell carcinoma in a North American population". Urology 79 (5): 1092–1097. May 2012. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2011.12.048. PMID 22386252.

- ↑ "WHO Disease and injury country estimates". World Health Organization. 2009. https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html.

- ↑ "Cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: estimated incidence of disease, nodal metastasis, and deaths from disease in the United States, 2012". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 68 (6): 957–966. June 2013. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.11.037. PMID 23375456.

- ↑ "Squamous Cell Carcinoma". T he Skin Cancer Foundation. 2018. https://www.skincancer.org/skin-cancer-information/squamous-cell-carcinoma.

- ↑ "Drinking Water Arsenic Contamination, Skin Lesions, and Malignancies: A Systematic Review of the Global Evidence". Current Environmental Health Reports 2 (1): 52–68. March 2015. doi:10.1007/s40572-014-0040-x. PMID 26231242.

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

|