History:Walls of Benin

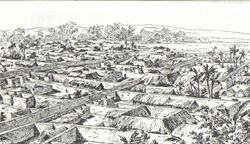

The Walls of Benin are a series of earthworks made up of banks and ditches, called Iya in the Edo language, in the area around present-day Benin City, the capital of present-day Edo, Nigeria. They consist of 15 km (9.3 mi) of city iya and an estimated total of 16,000 kilometres (9,900 miles) of rural iyas, probably used to divide lands and properties, in the area around Benin.[1] The walls of Benin City and surrounding areas were described as "the world's largest earthworks carried out prior to the mechanical era" by the Guinness book of Records.[2] Some estimates suggest that the walls of Benin may have been constructed between the thirteenth and mid-fifteenth century CE[3] and others suggest that the walls of Benin (in the Esan region) may have been constructed during the first millennium CE.[3][4]

Construction

Estimates for the initial construction of the walls range from the first millennium CE to the mid-fifteenth century CE. According to Connah, oral tradition and travelers' accounts suggest a construction date of 1450-1500 CE.[5] It has been estimated that, assuming a 10-hour work day, a labour force of 5,000 men could have completed the walls within 97 days, or by 2,421 men in 200 days. However, these estimates have been criticized for not taking into account the time it would have taken to extract earth from an ever deepening hole and the time it would have taken to heap the earth into a high bank.[6]

First mentions in Europe

The Benin City walls have been known to Europeans since about 1500, when Portuguese explorer Duarte Pacheco Pereira briefly described the walls during his travels:

The archaeologist Graham Connah suggests that Pereira was mistaken with his description by saying that there was no wall. Connah says, "[Pereira] considered that a bank of earth was not a wall in the sense of the Europe of his day."[8]

A century later, Dutch explorer Dierick Ruiters offered this account around 1600:[8]

At the gate where I entered on horseback, I saw a very high bulwark, very thick of earth, with a very deep broad ditch, but it was dry, and full of high trees... That gate is a reasonable good gate, made of wood in their manner, which is to be shut, and there always there is watch holden.[9]

Description

The walls were built of a ditch and dike structure; the ditch dug to form an inner moat with the excavated earth used to form the exterior rampart.

Scattered pieces of the structure remain in Edo, with the vast majority of them being used by the locals for building purposes. What remains of the wall itself continues to be torn down for real estate developments.[10]

Ethnomathematician Ron Eglash has discussed the planned layout of the city using fractals as the basis, not only in the city itself and the villages but even in the rooms of houses. He commented that "When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganised and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet."[11]

See also

- Ancient Kano City Walls

- Sungbo's Eredo

- Oba of Benin

References

- ↑ Patrick Darling (2015). "Conservation Management of the Benin Earthworks of Southern Nigeria: A critical review of past and present action plans". in Korka, Elena (in en). The Protection of Archaeological Heritage in Times of Economic Crisis. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 341–352. ISBN 9781443874113. https://books.google.com/books?id=B_imBgAAQBAJ&dq=Walls+of+Benin+&pg=PA353. Retrieved 9 March 2019.

- ↑ Koutonin, Mawuna (March 18, 2016). "Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace". The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/18/story-of-cities-5-benin-city-edo-nigeria-mighty-medieval-capital-lost-without-trace.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ogundiran, Akinwumi (June 2005). "Four Millennia of Cultural History in Nigeria (ca. 2000 B.C.–A.D. 1900): Archaeological Perspectives". Journal of World Prehistory 19 (2): 133–168. doi:10.1007/s10963-006-9003-y.

- ↑ MacEachern, Scott (January 2005). "Two thousand years of West African history". African Archaeology: A Critical Introduction (Academia). https://www.academia.edu/831918.

- ↑ Connah, Graham (January 1972). "Archaeology of Benin". The Journal of African History 13 (1): 33. doi:10.1017/S0021853700000244.

- ↑ Connah, Graham (June 1967). "New Light on the Benin City Walls". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 3 (4): 608. ISSN 0018-2540.

- ↑ Hodgkin, Thomas (1960). Nigerian Perspectives: An Historical Anthology. Oxford University Press. pp. 93. ISBN 978-0192154347.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Connah, Graham (June 1967). "New Light on the Benin City Walls". Journal of the Historical Society of Nigeria 3 (4): 597–599. ISSN 0018-2540.

- ↑ Hodgkin, Thomas (1960). Nigerian Perspectives: An Historical Anthology. Oxford University Press. pp. 120. ISBN 978-0192154347.

- ↑ "Home | Benin Moat Foundation". http://www.beninmoatfoundation.org/clarioncall.html.

- ↑ Koutonin, Mawuna (18 March 2016). "Story of cities #5: Benin City, the mighty medieval capital now lost without trace". https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/mar/18/story-of-cities-5-benin-city-edo-nigeria-mighty-medieval-capital-lost-without-trace.

External links